Nigel Parsons’ Family Travels – A Life Dream Come True?

July 22, 2013

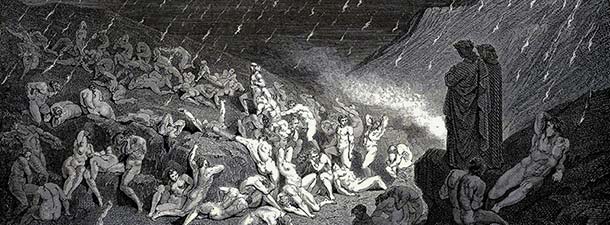

The Divine Comedy

August 1, 2013Sounding the alarm for the environment and the natural world is not unlike shouting “FIRE!” while witnessing a colossal blaze whose flames destroy all in their path and continue burning, in spite of every human effort to extinguish the inferno. Nonetheless, we will keep shouting at Dante precisely because the destruction of the planet is the most pressing issue of our time.

We will, of course, continue to debate the broad spectrum of cultural issues and current affairs and attempt to fulfil our humanistic imperative, implicit in our very name, as best we can for each issue, as we promised from the outset. But in offering our second green edition, we are also consciously strengthening our aim to build a tradition that recognises environmental and ecological journalism as one of the pillars of our identity.

The legendary BBC war correspondent Martin Bell, spoke of the “journalism of attachment” to describe his reportage during the conflict in the former Yugoslavia.

Explained succinctly, it was a journalism that rejected the notion of pure objectivity, which challenged the notion that all sides merited equal say or had equal moral value, in the context of the victim and the aggressor. We feel much the same way about the constant onslaught against the natural world and are unequivocal in choosing a side. We are also certain that we are not alone, that a global voice for sanity in the just preservation of the earth and all of its living patrimony grows stronger each year and will not be ignored.

We grasp of course that the ongoing protests in Turkey are at their core about democracy and its usurpation and abuse, but it is not lost on us that it all began as an effort to preserve Istanbul’s Taksim Gezi Park, that an effort to stop the bulldozers from annihilating one of the city’s last urban green spaces – and the brutality with which the Turkish government responded – prompted the Turkish civic uprising.

And leaving aside issues of journalism and its duties, is it not a matter for all democracies to safeguard the environment, to curb climate change, to ensure food and water security, to preserve a safe habitat for future generations, to strive for alternative clean energy and to put a halt to the biocide taking place on every continent?

By the end of the century, unless trends are reversed, half the known species currently in existence will be extinct. Some 16,000 species of plants, mammals, birds and all manner of other organisms will vanish forever. The consequences are incalculable, as the natural order will be damaged permanently. What will it do to us? Nothing good: some things we dare not even imagine. And we know what is to blame: climate change; overdevelopment and exploitation of the environment; monolithic agriculture like palm oil plantations or cattle pastures that destroy more than they replace and the wiping out of pristine habitats.

This year we crossed a terrible threshold, with carbon monoxide levels in the atmosphere reaching their highest levels ever in human history. The green house effect is not some controversial hypothesis. It is a terrifying truth and a scientific fact. And here is another inescapable fact: the central reality of much of this systemic and endemic damage is the result of greed – corporate avarice to be specific, the same corporate avarice that is undermining democracy itself in an unholy alliance between lawmakers and their corporate sponsors. It is tantamount to open, legalised corruption.

Thus oil companies spend untold millions striving to denigrate climate scientists and clean energy advocates, helping to block reform, and urging governments to criminalise those that oppose their plans for expansion from the Niger Delta to the Keystone XL pipeline in Canada and the US, and beyond. In the worst cases there is bloodshed, whether by the state or private security forces, and the routine violation of human rights.

And while we are on that subject, what can we make of the statement by Nestle’s CEO Peter Brabeck that potable, clean water is not a universal human right but a commodity subject to market forces and profitability? We feel the same about this terrifying and – it must be said – perverse understanding of capitalist imperative, as we do the recent bulldozing of a Mayan temple in Belize to help facilitate road building. We wish both were tales of fiction, but they are not.

This is the world we live in: a world where scientists primarily blame pesticides for the quiet honey bee holocaust taking place either side of the Atlantic. Bee populations that are experiencing “Colony Collapse Disorder” have death rates of between 30% and 90%. What will we do if the bees become extinct and stop pollinating? And yet the US Congress rallies to deliver legislation to protect Monsanto, one of the key manufacturers, users and distributors of pesticide and the leading champion of genetically modified food.

Yet we can be grateful that it is not a question of passive acceptance either on the street or in the seats of power. On May 25th millions of people all over the world marched against Monsanto in 52 countries and 436 cities. Germany has announced a long-term goal to dismantle all of its nuclear energy infrastructure. The Brazilian government has managed to curb the deforestation of the Amazon. Even China and India are starting to come to terms with the reality that all-out industrial development cannot continue with so little concern for environmental safeguards.

These are all hopeful signs but it is not nearly enough. There is much more to do and we have left it so late. To truly save the planet requires such profound reform that it means nothing less than reshaping the whole of so-called civilisation as we know it. Can we do that? We must certainly make the attempt, for in saving the planet we save humanity – not just ourselves, but generations to come.

The Iroquois Nations of North America included, as part of their oral constitution, that they would, before making any decision (about land-use or otherwise), consider what might be the consequences of that decision for seven generations into the future. It is a lesson that modern humanity could learn from a people who understood – well before modernity – that we are all connected. What we do now reverberates into the future. We have an absolute obligation to preserve this world for those to come – and to do so better than it was preserved for us.