Pandoro or Panettone? Let Us Eat Cake!

December 3, 2019

THE LAST AFRICAN COLONY

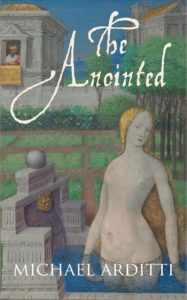

May 12, 2020Massimo Gava interviews DANTE favourite, Michael Arditti, about his new novel, The

Anointed. The Anointed is a beautiful, bold and imaginative retelling of the story of King

David and his wives. The characters are as compulsive and vivid as those in a

contemporary dynastic saga such as Succession, but Arditti’s brilliant writing roots them in a

fully authentic biblical world.

So, Michael, the first and obvious question is ‘Why King David?’

It’s simple. He’s a boundlessly intriguing, complex, contradictory and elusive figure, just

right for literary exploration. Did you know that there’s more about him than anyone else in

the Old Testament? And more about him than anyone other than Jesus in the entire Bible?

Every child knows the story of David and Goliath. If you’re religious, you’ll know that

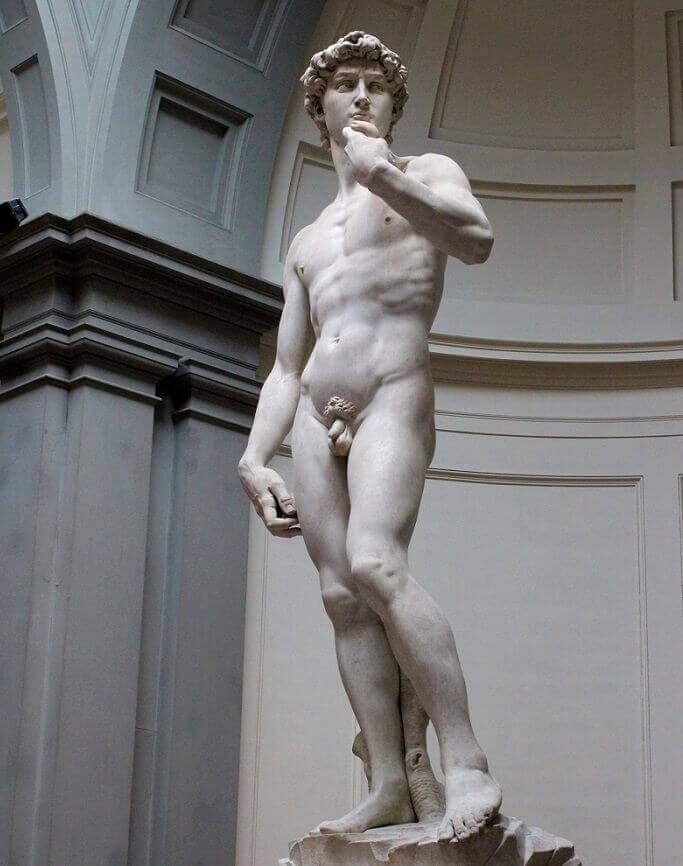

he’s reputed to have written the Psalms. If you’re an art lover, you’ll know the many

paintings of David and Bathsheba. And, of course, the whole world knows Michelangelo’s

statue of David in Florence.

But do they know – do you know – that the legendary king of

Israel was also a traitor who’d allied himself with the Philistines? Do they know that the

man who brought the Ark of the Covenant to Jerusalem and famously danced near naked in

front of it was regarded by God as too sinful to build the Temple? Do they know that the

man who inflicted lasting defeat on the country’s enemies and united the warring tribes

failed to control his own children, one of whom led a rebellion against him and another of

whom raped his half-sister?

So, is he a mythical figure like Abraham and Moses or did he actually exist?

He is generally held to have been born around 1000 BC. I think I’m right in saying that the

first Hebrew king for whom there is independent evidence is Ahab, whose defeat in battle is

inscribed on an Assyrian monolith about a century later. But there has been a very exciting

recent archaeological discovery of an Aramaean tablet, which refers to the death of Ahab’s

son, Jehoram, ‘king of Israel and king of the house of David.’ This would appear to

authenticate the biblical David.

And your own view?

I am convinced that there was a 10th century BC king of Israel called David. If you were

inventing a hero – and, remember, he is the great Old Testament hero – you wouldn’t invent

one with such glaring faults. He betrayed King Saul, who’d favoured him and married him

to his daughter; he abandoned her and murdered either her or her sister’s children (the text

is ambiguous); he stole the wife of one of his army captains, whose death he then

engineered; he alternately neglected and indulged his children. Moreover, at the end of his

life he proved to be impotent, failing to avail himself of the young virgin who was brought,

in the Bible writer’s euphemistic phrase, ‘that my lord the king may get heat’, and this was

at a time when the king’s virility symbolized that of the nation.

So, you regard the Biblical account as a historical record?

No, I didn’t say that or, if I did, I didn’t mean to. I am quite sure that there was a king

named David, but the Biblical account, which would have assumed its final form two or

three hundred years after the events described, is a literary construct. For a start, the two

distinct religious traditions of Israel and Judah have been amalgamated, not always

seamlessly, and there is obvious exaggeration in the numbers of soldiers, sacrifices, wives

and concubines mentioned. And it’s no accident that David took on his basic literary form

at much the same time as Odysseus. They are the two richest, most engaging and most

tantalising figures of the Ancient World.

Yet contemporary writers are constantly revisiting the story of Odysseus and the Trojan

war; I can’t say the same about David.

That’s because the literary world is essentially hostile to religion. When people think of the

Old Testament, they think of scripture lessons at school. But the story of David – the

shepherd boy who rose to become a great king – is endlessly dramatic. It’s filled with

familial, marital and national struggles. It’s both intimate and epic, contemplative and

adventurous. And I assure you that the story of Bathsheba is every bit as erotic as that of

Helen of Troy!

In which case I’m surprised there have been so few reworkings of the story.

I wouldn’t want to mislead you; there have been quite a few. Richard Gere starred in an

inept Hollywood film that singlehandedly destroyed the biblical epic. Tim Rice wrote a

musical with Disney composer, Alan Menken, which failed to emulate the success of

Joseph. And there’ve been several novels, the most celebrated of which is Joseph Heller’s

God Knows. This purports to be David’s deathbed memoir and, among much else, has him

anachronistically complaining that Michelangelo portrayed him with an uncircumcised

penis!

I take it you don’t approve.

It’s not so much that I don’t approve, rather that I find it facetious. The joke palls very

quickly. The story is rich and rousing enough without the need to resort to such literary

tricks.

Given that these other versions exist, what is it that you bring to the story?

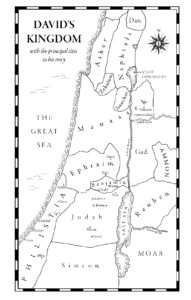

Women, in a word. I tell the story from the perspective of three of David’s wives. The first

is Michal, the young, innocent daughter of King Saul and sister of Jonathan, whom David

loved ‘passing the love of women’. The second is Abigail, a wealthy widow, who provided

David with a power base and smoothed his path to the throne. The third is Bathsheba,

whom David spied bathing naked on her roof, whom he stole from her husband and who

ultimately outwitted him.

Why did you choose to tell the story in this unusual way?

Well, one reason is precisely that it is unusual! For a writer, one of the main attractions of reworking a familiar story is to ring the changes on it. I swiftly realised that the whole of David’s story could be told through the voices of the three women and that their differing perspectives would explain many of the contradictions in David’s character and conduct.

As a man, are you worried about charges of cultural appropriation?

My main worry is that you feel the need to ask the question! A writer must be free to follow

his or her imagination. It is for the reader to tell us whether or not we have succeeded. I

abhor the current trend to censor – neuter – writers. It’s a sort of literary fascism. I don’t

need to tell you how many great novels about women have been written by men and vice

versa. Literature should be about pulling down barriers, not putting them up.

I can tell that you feel very strongly about this. I’ve seen the book described as ‘#MeToo

meets the Old Testament’. That all sounds highly contemporary. How true have you been

to the women and, indeed, the whole story as it appears in the Bible?

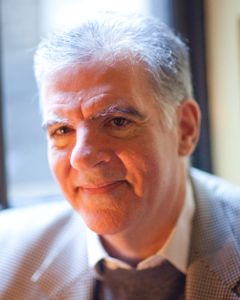

Michael Arditti

I’m delighted that people have found that a story (or, perhaps I should say, the treatment of a story), which dates from 3000 years ago, continues to have power and resonance. If I can refer to a note that I’ve placed at the front of the book: “I have adhered strictly to the sequence of events in the Books of Samuel. I have, however, felt free to add and amplify characters, to reinterpret incidents and resolve inconsistencies, making a contemporary fiction out of an ancient myth.” The Old Testament is predominantly a book about men (and a male God), written by men for men. With a couple of exceptions, the women are either wicked seductresses or devoted mothers. Michal, Abigail and Bathsheba, although crucial figures in David’s life, remain oblique to the biblical account of it. It is as if the scribes who originally wrote the story, were reluctant to open the doors of the harem. In focussing on the women, I’ve tried both to bring the women out from the shadows and set the record straight.

I have to admit that I didn’t know much of the biblical story before I started it. Having

finished it, I must congratulate you on having written a wonderfully rich, original, profound and absorbing novel. Thank you. Now, one final question: the world is currently facing its worst health crisis in over a century; does The Anointed address that in any way?

I hope that, like any good novel, it will help to sustain readers during the pandemic, as well as taking them on an imaginative journey when all others are strictly curtailed. But I realise that it’s a trick question because, as you know, David’s kingdom is afflicted by plague. But I doubt that even the most draconian current leader would choose to deal with it as David does, by hanging the seven sons of his rivals!

The Anointed is published by Arcadia (£16.99) and is currently available from Amazon,

Waterstones.com and all independent bookshops.

www.michaelarditti.com